Sustainable Textiles from Agro-Waste: Development and Performance Evaluation of Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF) Blended Yarns and 100% Cotton

Abstract

1, Ragib Mahbub 2, Md Kowsar Alam

3* ,Engr. Md. Abu

Sayed4

1Textile Engineering

College, Zorargonj, Chattogram

2Textile

Engineering College, Zorargonj, Chattogram

3Textile Engineering

College, Zorargonj, Chattogram

4Dept. of Yarn

Engineering, Textile Engineering College, Zorargonj, Chattogram

Corresponding author’s e-mail address: Kowsaralam017@gmail.com

Rising global demand for sustainable textiles is driving attention toward innovative natural fibers, among which Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF) stands out for its exceptional tensile strength, natural luster, and complete biodegradability. In Bangladesh, where the spinning sector remains heavily reliant on costly cotton imports, Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF) presents a locally available, environmentally sustainable alternative with the potential to reduce import dependence, optimize the utilization of indigenous resources, and convert agricultural waste into value-added products. Pineapple cultivation produces abundant 3-ft leaves, often discarded or used as low-value fodder despite their strong fiber potential. This study evaluates PALF–cotton and PALF–polyester yarns, produced via conventional ring spinning, against 20 Ne 100% cotton, assessing key Uster® parameters including unevenness, CVm%, hairiness, defects, and elongation. The 100% cotton yarn demonstrated the highest uniformity (U% = 8.63) and minimal defect incidence, while blends particularly cotton–PALF exhibited greater irregularities (U% = 12.24). Nevertheless, elongation properties improved markedly in blends (8.53% for cotton–PALF; 9.66% for polyester–PALF vs. 5.83% for cotton) with hairiness maintained within acceptable thresholds. The results, analyzed through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) using the SU1510 model from Japan, underscored PALF’s strategic role in enabling zero-waste manufacturing, upcycling agricultural residues into premium textile products, and advancing Bangladesh’s fiber independence under a sustainable production model.

Keyword: Sustainable, Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF), Biodegradability, zero-waste

Full Text

1.0 Introduction:

In recent years, world focus on sustainability and the shift toward greener technologies has intensified, with polymers and fiber composites emerging key contributors to environmentally friendly technological advancements. (Cislaghi et al., 2021). Most of the plant fiber have emerged as promising alternatives to synthetic and cotton fibers, providing affordable, lightweight, and biodegradable options that help reduce waste and conserve natural resources. (Ramamoorthy et al., 2015). Also, plant-based natural fibers favorable mechanical properties, energy efficiency, and worldwide abundance. They also support rural economies and cause less machinery wear and health risk. Among them, pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) is notable for its polymer reinforcement potential, despite being an agricultural by-product (Glória et al., 2017). The Kew variety of PALF contains about 70–82% holocellulose, 5–12% lignin, and 1.1% ash (Sharma, U et al 1981) . Its high cellulose and crystalline structure give it strong mechanical performance (Yu, 2001). Studies also show tensile strength of 362–748 MN·m⁻² and modulus of 25–36 GN·m⁻², confirming PALF’s excellent reinforcing potential (Mukherjee & Satyanarayana, 1986). Yu (Yu, 2001) found that pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) has physical and structural properties like ramie, flax, and jute. It contains about 56–62% cellulose, 16–19% hemicellulose, and 9–13% lignin, giving it good strength and stiffness for textile use. These proportions suggest that PALF possesses a balanced combination of cellulose and lignin, contributing to its moderate strength, stiffness, and potential suitability for textile and composite applications. (Yu, 2001), PALF fibers are 3–8 mm long, 7–18 μm in diameter, and have a density of 1.543 g/cm³. The fibers are white and silky, traditionally used in weaving (Robin et al., 2011). PALF is coarse and hard to spin into fine yarn, but its low cost and large diameter make it a good alternative to jute. (Jalil et al., 2021). It is also used in decorative and blended fabrics r.(Hazarika et al., 2018a). Another study (Devi et al., 1997a)examined the mechanical behavior of PALF–polyester composites, considering factors such as fiber loading, fiber length, and surface treatment. Their results showed that tensile and impact properties improved with higher fiber content, while flexural strength was optimized at lower fiber loadings.

Table 1. Comparative Evaluation of Physical and Optical Properties of Retting and Degumming Treatments on Fiber (Hazarika et al., 2018b); (Jose et al., 2019).

|

Parameter |

Retted Fiber |

Degummed Fiber |

|

Color strength (K/S) |

2.5 |

2.9 |

|

Whiteness index |

59 |

56 |

|

Yellowness index |

50 |

46 |

|

Brightness index |

35 |

30 |

|

Moisture regains (%) |

7.6 |

9.8 |

|

Water absorbency (s) |

21 |

10 |

As an agricultural by-product, pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) offers sustainable, low-cost, and biodegradable material. Its use in composites and fiber blends minimizing production costs and uprising material performance. In Bangladesh, spinning industry mostly depends on imported cotton, adopting locally available PALF provides a practical way to reduce import cotton and promote economic sustainability. This study explores the potential of PALF as a renewable textile raw material, focusing on producing cotton–PALF–polyester blended yarns using the existing spinning system without any additional setup, to improve yarn quality while supporting farmers and adding value to agricultural waste.

2.0 Methodology

2.1 Raw Materials:

Cotton: The properties of the cotton which was used in the study as follows.

Table 2. Average HVI Results of Ivory Coast Cotton Fiber

|

Fiber Property |

Mean Value |

|

Spinning Consistency Index (SCI) |

126 |

|

Staple Length |

28.09 mm |

|

Fiber Strength |

31.0 g/tex |

|

Elongation (%) |

6.5 |

|

Micronaire Reading |

4.39 |

|

Fiber Fineness (tex) |

0.16 |

|

Short Fiber Index (SFI) |

6.2 |

|

Short Fiber Content (SFC %) |

9.2 |

|

Color Grade (CG) |

Strict Low Middling (42–2) |

Polyester: In this study, polyester fiber was blended with PALF obtained from Matin Spinning Mills Ltd. for experimental and testing purposes. The properties of the polyester staple fiber used in the investigation are presented as follows:

Table3: test results of polyester fiber properties

|

Fiber properties |

value |

|

Fineness |

1.4 dtex |

|

Fibre Length |

38mm |

Pineapple Fiber: Accordingly, the properties of pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) analyzed in this study are derived from previously published literature and are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Physio-mechanical properties Retting and Degumming Processed Fibers of PALF (Jose et al., 2019)

|

Fiber Type |

Fineness (tex) |

Bundle Strength (Pressly Index, kg/mg) |

Tenacity at Break (gf/tex) |

Elongation at Break (%) |

|

Retting Fiber |

4.1 (23) |

4.89 (19.04) |

31.32 (31) |

4.5 |

|

Degummed Fiber |

3.5 (31) |

4.21 (23.01) |

25.29 (27) |

6 |

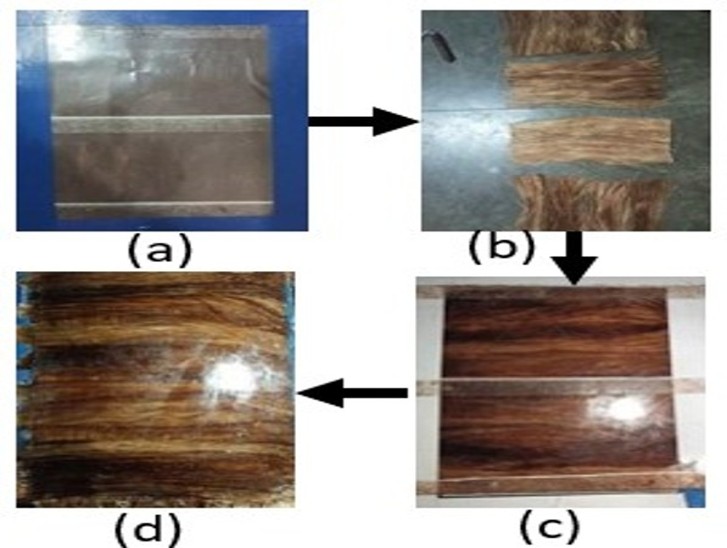

2.2 PALF Extraction

Manual Extraction: Fibers were scraped from pineapple leaves using a knife, though ceramic plates or coconut shells may also be used. An experienced worker can process over five hundred leaves per day; however, the method is labor-intensive, causes significant fiber loss, and requires subsequent washing and open-air drying.

Mechanical Extraction: The prickly edges of the leaves are first removed with a knife, after which the leaves are processed in a conventional decorticator machine. The scratching roller blades strip the waxy surface layer, and the serrated roller macerates the leaf, creating breaks that facilitate microbial retting

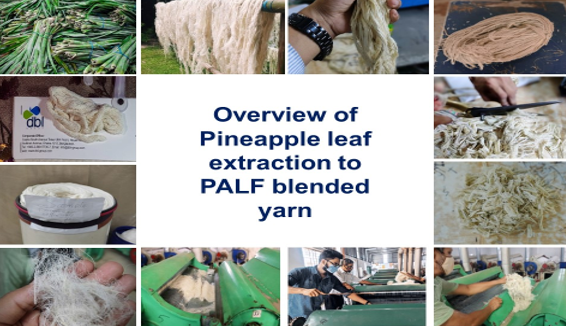

Figure 1. Overview of the process from pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) extraction to blended yarn production. The images depict successive stages including collection of pineapple leaves, fiber extraction, washing, drying, cutting, and blending with cotton and polyester fibers, followed by spinning and preparation of final yarn samples

2.3 Blending Process

PALF Preparation and Softening Process

Raw pineapple leaf fiber (PALF), with a staple length of 0.5–1 m like jute, is naturally coarse and unsuitable for blending. To prepare the fiber, it was first dried, then cut into lengths of 38 mm using a knife and lightly moistened with normal water. The fibers were subsequently processed in a recycling shredding machine, where they were passed through the last five rollers three times (15 passes in total). This treatment reduced the harshness of the fibers, producing a softer texture more comparable to cotton and suitable for blending with other fibers. The softened PALF was then manually blended with cotton in the blowroom and processed through subsequent operations as shown in the flowchart (figure.2)

Figure.2 Flow diagram of the spinning process for cotton–PALF (95:5) and polyester–PALF (95:5) blended yarns using the existing spinning system. Raw PALF was shredded into fine fibers and blended with cotton or polyester, followed by carding, drawing, simplex, and ring spinning operations.

2.4 Process of PALF-Blended Yarn Production

To produce blended spun yarn, standard spinning machinery was employed, beginning with blowroom processing and followed by carding, drawing, simplex, and ring spinning. The detailed machine settings for both cotton–PALF and polyester–PALF blends are summarized in Table 5, while the actual yarn counts obtained are presented in Table 6.

Table 5. Process Parameters for PALF-Blended Yarn Production

|

Stage |

Parameters |

Cotton–PALF |

Polyester–PALF |

Output |

|

Blowroom |

Same process |

Same process |

Opened & cleaned fiber |

|

|

Carding |

55 kg/hr.; Grain/yard: 101; Gauge: 0.35 cm |

Cylinder speed: 875 rpm |

Cylinder speed: 800 rpm |

Carded sliver |

|

Breaker Drawframe |

Grain/yard: seventy-five; Drafting & Roller gauge |

Draft:8; Gauge: 38×43 |

Draft: 5; Gauge: 44×48 |

Breaker-drawn sliver |

|

Finisher Drawframe |

Grain/yard: 75.50; Drafting: eight; Roller gauge |

38×43 |

44×48 |

Finisher-drawn sliver |

|

Simplex Frame |

Roving hank: 0.78; TPI: 1.07 |

Same settings |

Same settings |

Roving |

|

Ring Frame |

Draft: 27.179; TPI: 15.20; Nominal count: 20 Ne |

Actually: 20.57 Ne |

Actually: 19.93 Ne |

Yarn |

Table 6. Actual Yarn Count of Produced Samples

|

Sample Type |

Actual Count (Ne) |

|

100% Cotton Yarn |

19.64 |

|

Cotton–PALF Blend |

20.57 |

|

Polyester–PALF Blend |

19.93 |

2.5 Method of testing

USTER Tester 6 :

The USTER Tester 6, recognized internationally as the benchmark instrument for yarn quality assessment, was employed in this study to ensure precise and standardized evaluation. Five samples of 20 Ne yarns comprising 100% cotton, cotton–PALF, and polyester–PALF blends evaluated for key quality parameters, including unevenness (U%), coefficient of mass variation (CVm%), hairiness, and the incidence of thick, thin, and Neps..

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis:

To examine the surface morphology and structural characteristics of the produced yarns, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed. The yarn samples, including 100% cotton, cotton–PALF, and polyester–PALF blends, were prepared and analyzed using the SEM SU1510 model (Japan) in DUET textile lab. The analysis focused on identifying surface irregularities, fiber bonding, and the overall texture of the yarns. High-resolution images were captured at various magnifications to observe both macro and microstructural features.

2.6 Cost Analysis

Table 7. Cost Comparison of PALF–Cotton, PALF–Polyester, and 100% Cotton Yarns

|

Expense Incurred |

Cotton–PALF (95:5) (USD) |

Polyester–PALF (95:5) (USD) |

100 % Cotton (USD) |

|

Cotton fiber |

2.12 |

– |

2.23 |

|

Polyester fiber |

– |

1.00 |

– |

|

Pineapple fiber (5 %) |

0.63 |

0.63 |

– |

|

Fuel cost (United Group) |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

|

Overhead cost (excluding fuel) |

0.13 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

|

Total Cost (USD/kg) |

2.95 |

1.83 |

2.43 |

Figure 3: Comparison of total production cost (USD per kg) among Cotton–PALF (95:5), Polyester–PALF (95:5), and 100% Cotton yarns.

3.0 Results and Discussion

3.1 Observations Uster® Testing:

These SEM images analyzed in conjunction with the results from the Uster® testing. The cotton-PALF blend showed a higher unevenness (U% = 12.24) compared to the polyester-PALF blend (U% = 10.05), aligning with the irregularities observed in the SEM images. Additionally, the elongation properties were more pronounced in the polyester-PALF blend (9.66%) compared to the cotton-PALF blend (8.53%), further corroborating the smoother and more uniform texture shown in the SEM images.

Table 8. Yarn Properties of 100% Cotton, Cotton–PALF (5%), and Polyester–PALF (5%) Blends

|

Property |

100% Cotton |

Cotton–PALF (5%) |

Polyester–PALF (5%) |

|

Unevenness (U%) |

8.63 |

12.24 |

10.05 |

|

Thin places (-30%/km) |

297 |

2295 |

430 |

|

Thick places (+50%/km) |

16 |

338 |

242 |

|

Neps (+200%/km) |

32 |

368 |

254 |

|

Hairiness (H index) |

6.64 |

6.78 |

6.42 |

|

Elongation (%) |

5.83 |

8.53 |

9.66 |

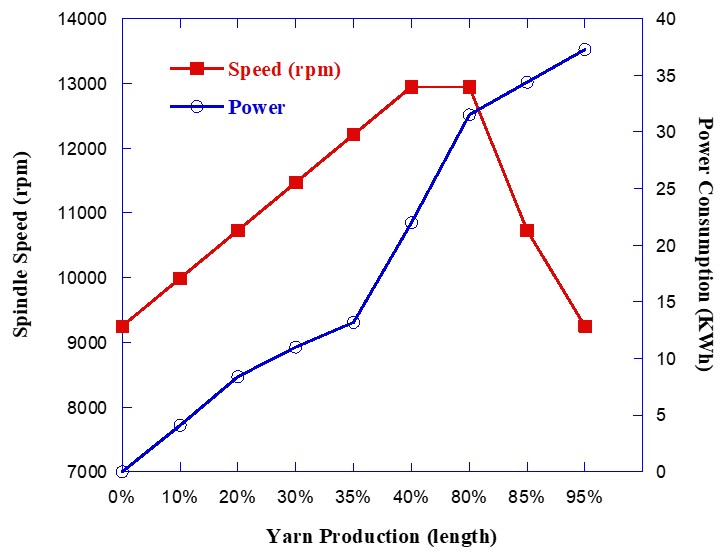

Pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) demonstrates good mechanical strength and, when blended with cotton or polyester, serves as a cost-effective material with considerable potential for diverse industrial and textile applications. In Figure 4, illustrates that cotton–PALF blends exhibited imperfections, particularly thin places (2295/km), compared to 100% cotton (297/km). In contrast, polyester–PALF blends showed fewer imperfections, performing better than cotton–PALF. These findings align with earlier literature and suggest that PALF blends can also be applied in furnishings and decorative textiles, broadening their use in the clothing sector. (Hazarika et al., 2018c).

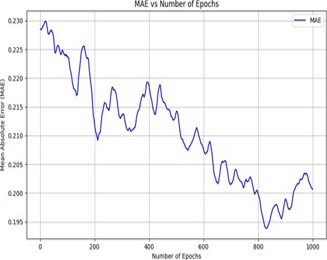

As shown in Figure 5, unevenness rose sharply in cotton–PALF yarns (12.24) versus 100% cotton (8.63), consistent with earlier findings that natural fiber stiffness reduces uniformity (Devi et al., 1997b). Polyester–PALF blends showed only a moderate increase (10.05), suggesting better compatibility. Hairiness remained stable across all yarns, while elongation improved in both blends, reaching a maximum in polyester–PALF (9.66), these results are consistent with earlier literature, which reported enhanced flexibility and tensile performance in synthetic fiber blends.

3.2 SEM Analysis Results:

The Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis provided valuable insights into the surface morphology and structural features of the yarns. The following SEM images illustrate the differences in surface features, fiber bonding, and overall texture for the three yarn types: 100% Cotton, Cotton-PALF, and Polyester-PALF blends.

• Figure 6a (Cotton–PALF):

The SEM micrograph reveals surface irregularities with rough patches in the fiber structure. The incorporation of PALF, a coarser fiber, disrupts yarn uniformity.

• Figure 6b (Cotton–PALF, higher magnification):

Fiber alignment is evident, but bonding between cotton and PALF is inconsistent. Localized weak adhesion may compromise yarn strength and smoothness.

• Figure 6c (Polyester–PALF):

The SEM image shows improved fiber alignment and a smoother surface compared to cotton–PALF. Polyester demonstrates better compatibility with PALF, resulting in more consistent texture.

• Figure 6d (Polyester–PALF, higher magnification):

Enhanced bonding and alignment are observed, with fewer irregularities. The polyester–PALF blend exhibits superior interfacial adhesion and surface uniformity relative to cotton–PALF.

4.0 Conclusion

This study demonstrated that pineapple leaf fiber (PALF) can be blended with cotton and polyester using conventional spinning machinery, requiring no major modifications. The blends improved yarn performance, particularly in elongation, and showed potential for producing fancy and value-added textiles. Adoption of PALF could reduce dependence on imported fibers, generate economic benefits, and promote sustainability by converting agricultural waste into a valuable resource.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge all the lecturers and teachers at Textile Engineering College, Zorargonj, Chattogram, for their invaluable guidance, constructive feedback, and constant encouragement throughout this research. We are also grateful to DBL Group, Bangladesh, and DUET Textile Lab for providing essential technical assistance and laboratory facilities that significantly contributed to the successful completion of this work.

References:

Cislaghi, A., Sala, P., Borgonovo, G., Gandolfi, C., & Bischetti, G. B. (2021). Towards More Sustainable Materials for Geo-Environmental Engineering: The Case of Geogrids. Sustainability, 13(5), 2585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052585

Devi, L. U., Bhagawan, S. S., & Thomas, S. (1997a). Mechanical properties of pineapple leaf fiber-reinforced polyester composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 64(9), 1739–1748. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970531)64:9%253C1739::AID-APP10%253E3.0.CO;2-T

Devi, L. U., Bhagawan, S. S., & Thomas, S. (1997b). Mechanical properties of pineapple leaf fiber‐reinforced polyester composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 64(9), 1739–1748.

Glória, G. O., Teles, M. C. A., Lopes, F. P. D., Vieira, C. M. F., Margem, F. M., Gomes, M. D. A., & Monteiro, S. N. (2017). Tensile strength of polyester composites reinforced with PALF. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 6(4), 401–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2017.08.006

Hazarika, P., Hazarika, D., Kalita, B., Gogoi, N., Jose, S., & Basu, G. (2018a). Development of apparels from silk waste and pineapple leaf fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers, 15(3), 416–424.

Hazarika, P., Hazarika, D., Kalita, B., Gogoi, N., Jose, S., & Basu, G. (2018b). Development of apparels from silk waste and pineapple leaf fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers, 15(3), 416–424.

Hazarika, P., Hazarika, D., Kalita, B., Gogoi, N., Jose, S., & Basu, G. (2018c). Development of apparels from silk waste and pineapple leaf fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers, 15(3), 416–424.

Jalil, M. A., Moniruzzaman, M., Parvez, M. S., Siddika, A., Gafur, M. A., Repon, M. R., & Hossain, M. T. (2021). A novel approach for pineapple leaf fiber processing as an ultimate fiber using existing machines. Heliyon, 7(8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07861

Jose, S., Das, R., Mustafa, I., Karmakar, S., & Basu, G. (2019). Potentiality of Indian pineapple leaf fiber for apparels. Journal of Natural Fibers.

Mukherjee, P. S., & Satyanarayana, K. G. (1986). Structure and properties of some vegetable fibres: Part 2 Pineapple fibre (Anannus comosus). Journal of Materials Science, 21(1), 51–56.

Ramamoorthy, S. K., Skrifvars, M., & Persson, A. (2015). A Review of Natural Fibers Used in Biocomposites: Plant, Animal and Regenerated Cellulose Fibers. Polymer Reviews, 55(1), 107–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583724.2014.971124

Robin, G., Pilgrim, R., Jones, S., & Etienne, D. (2011). Caribbean Pineapple Production and Post Harvest Manual. Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute, 1–60.

S0008-6215%2800%2980678-3 (1). (n.d.).

Georgia Reader Reply

Et rerum totam nisi. Molestiae vel quam dolorum vel voluptatem et et. Est ad aut sapiente quis molestiae est qui cum soluta. Vero aut rerum vel. Rerum quos laboriosam placeat ex qui. Sint qui facilis et.