The Effect of Increasing Polyester Content on Air Permeability in Wool Woven Fabrics

Abstract

Gül ÖZKAN

Fashion Design Program, Istanbul Nişantaşı University, Istanbul, Türkiye

*Corresponding Author: Gül ÖZKAN, gul.seyhan@nisantasi.edu.tr

Received: 21 January 2026, Revised: 30 January 2026, Published: 14 February 2026

Abstract

Air permeability is a critical performance parameter in determining thermophysiological comfort in clothing products. It is also directly related to the structural properties of the fabric and its fiber composition. Wool-polyester blend woven fabrics are among the common clothing materials that aim to meet both comfort and durability requirements through the combined use of natural and synthetic fibers. Literature findings indicate that the natural crimped structure and high volume-forming capacity of wool fibers increase fabric porosity, thereby positively affecting air permeability. In contrast, the smooth surface structure and more compact arrangement tendency of polyester fibers reduce the inter-fiber void volume and limit air flow. Based on the literature, it is possible to state that as the polyester content increases, the fabric porosity decreases, leading to statistically significant reductions in air permeability values. The effect of polyester content on air permeability in wool blend woven fabrics should be evaluated in conjunction with parameters such as fiber type, fiber content, yarn properties, and weave structure. Depending on the desired comfort level in clothing products, the polyester ratio must be carefully determined, and it is understood that more comprehensive experimental studies are needed in the literature to determine the optimal fiber ratios. In this study, the findings indicate that the polyester content and changes in the structural properties of wool/polyester blended woven fabrics lead to measurable differences in air permeability values and are significant in terms of garment comfort.

Keywords: Wool, Polyester, Air permeability, Wearing comfort

Full Text

1. Introduction

Comfort in clothing products is directly related to the physical and thermos physiological properties of the textile material. Among these properties, air permeability plays a critical role in heat and moisture transfer by regulating air circulation between the garment and the environment [1,2]. Air permeability is defined as the amount of air passing through a unit area of fabric under a specific pressure difference and is considered one of the fundamental parameters determining the perception of comfort, particularly in clothing products [3]. Wool fibers enable the formation of highly breathable fabric structures due to their naturally crimped structure, high elasticity, and ability to create volume between fibers [4]. In other words, the distinctive feature of woolen woven fabrics is the high porosity they create within the fabric due to the naturally crimped structure of the fibers. This porous structure allows air flow, increasing the breathability of the fabric [5,6]. The elastic nature of wool fibers contributes to the continuity of air permeability by enabling the fabric structure to return to its original form after mechanical stress. Polyester fibers can lead to more compact fabric structures due to their smooth surface structures, low moisture absorption capacity, and high dimensional stability. Polyester fibers also tend to have a tighter arrangement in yarn and fabric structures due to their lower fiber twist and smooth fiber surface. The literature reports that the more compact arrangement of fibers reduces the volume of micro-voids within the fabric, which in turn decreases air permeability [7,8]. In this context, examining the effect of increasing the polyester content in wool-polyester blended woven fabrics on air permeability is important for evaluating the comfort performance of clothing products. Therefore, changes in the fiber content of wool-polyester blends lead to significant differences in the internal structure of the fabric. A review of the literature reveals that studies have shown that air permeability is primarily related to fabric porosity [9,10]. Fatahi and Yazdi (2018), in their study conducted on woven fabrics with different fiber blends, observed a statistically significant decrease in air permeability values as the synthetic fiber content increased. Majumdar et al. (2021) reported that increasing the synthetic fiber content in wool–synthetic blended woven fabrics reduces fabric porosity, leading to a statistically significant decrease in air permeability values. Similarly, Huang et al. (2022) reported that as the polyester content increased, the fabric structure became more compact, resulting in a decrease in air permeability. Li and Hu (2019) reported in their experimental study on wool–polyester fabrics with different blend ratios that air permeability values decreased significantly when the polyester content exceeded 50%. However, some studies have shown that blends containing 50% polyester can increase structural stability, making airflow more homogeneous, and that optimal comfort performance can be achieved at certain ratios [15,2]. This indicates that the effect of the polyester ratio is not linear and must be evaluated in conjunction with the structural parameters of the fabric. Air permeability measurements on wool blend woven fabrics are mostly performed in accordance with ISO 9237 and ASTM D737 standards [3;16]. In these standards, the volume of air passing through a unit area of the fabric under a specific pressure difference is measured, and the results are expressed quantitatively.

The literature also emphasizes that fabric weight, thickness, and weave density must be controlled in order to accurately determine the effect of fiber blend ratios [17,18]. Breathability is an important comfort parameter in clothing products, especially for outerwear and suit fabrics. While increasing the polyester content in wool-polyester blended woven fabrics offers advantages in terms of durability and ease of care, it has been reported that high synthetic content can reduce breathability and negatively affect thermal comfort [19,20]. For this reason, when determining the polyester content in clothing applications, not only cost and durability criteria but also breathability and user comfort must be taken into account.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, a quantitative research method was used to determine the effect of increasing polyester blend ratios in wool/polyester woven fabrics on the air permeability of clothing comfort properties. The material for the research consists of four types of wool/polyester blend woven fabrics of the same weave type (Twill weave) but with different thicknesses, weights, densities, and yarn counts, and the air permeability resistance data obtained from these fabrics. The fabrics were obtained from Yünsa Wool Industry and Trade Inc. The physical fabric parameters of the four types of wool/polyester blend woven fabrics used in the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Physical Properties of Wool/Polyester Woven Fabrics

|

Fabric Code |

Weave Type |

Mixing Ratio |

Weight (g/m²) |

Weft Density (counts/cm) |

Warp Density (counts/cm) |

Fabric Thickness (mm) |

Yarn Count (Nm) |

Warp Yarn Number (Nm) |

|

K1 |

Twill Weaving 2/1 |

65/35 Wool/ Polyester |

147 |

28 |

30 |

0.253 |

50 |

44 |

|

K2 |

Twill Weaving 2/2 |

65/35 Wool/ Polyester |

164 |

29 |

30 |

0.246 |

51 |

47 |

|

K3 |

Twill Weaving 2/1 |

50/50 Wool/ Polyester |

140 |

26 |

27 |

0.216 |

60 |

37 |

|

K4 |

Twill Weaving 2/2 |

50/50 Wool/ Polyester |

164 |

28 |

32 |

0.286 |

62 |

36 |

In addition to these properties, the known characteristics of wool and polyester fibers in the literature are as follows: Wool fiber thickens as it lengthens and shortens as it thins. The length and fineness of wool fiber varies depending on the breed of animal and the region of the fleece. Polyester fiber, which belongs to the synthetic and filament-based fiber group, is also known to be produced in the desired length and fineness.

The fabrics were first tested for weight and thickness at the Marmara University physical testing laboratory. The warp and weft densities were determined by counting with a magnifying glass per cm, and the warp and weft yarn counts were calculated using the data obtained. Fabric thickness was measured according to the EN ISO 5084:1996 standard accepted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

The fabric thickness was determined by measuring the samples with a fabric thickness measuring device at a pressure of 10g/cm2 with an accuracy of 0.01 mm and taking the arithmetic mean of the repeated measurement results for each sample. Fabric weight was measured according to the EN (European Norm) 12127:1997 standard accepted by CEN (European Committee for Standardization). Samples cut with a circular sample cutter were weighed with a precision scale; the weights per unit area of the fabrics were calculated to determine the grammage values. The values are the average of three measurements taken from different areas of the fabrics from all samples, using devices calibrated prior to measurement.

2.2. Methodology

Air permeability resistance measurements were performed using the Sdl-Atlas Air Permeability Tester device at the Ekoteks1 Textile Laboratory for data collection purposes.

Measurements were performed in accordance with ISO 9237 standard on the air permeability testing device. Air permeability resistance measurement results were obtained from a 5cm2 surface area at 100 Pascal pressure from the device.

Three measurements were taken from different areas of the fabrics using devices calibrated prior to measurement. Average values were calculated and compared. The air permeability of the fabrics, measured using an Sdl-Atlas brand air permeability resistance measuring device, is expressed in liters/square meter/second, and the measurement results are presented in Table 2 in the Results and Discussion section.

Figure 1. SDL Atlas Air Permeability Tester

3. Results and Discussion

Table 2. Air Permeability Resistance Measurement Results for Wool/Polyester Woven Fabrics Obtained from the Sdl – Atlas Air Permeability Tester Device

|

Fabric Code |

Measurement 1 |

Measurement 2 |

Measurement 3 |

Average Air Permeability Resistance (lt/m²/s) |

|

K1 |

152 |

153 |

146 |

150,3 |

|

K2 |

52,3 |

58,7 |

51,2 |

54,07 |

|

K3 |

189 |

155 |

195 |

179,7 |

|

K4 |

116 |

116 |

109 |

113,7 |

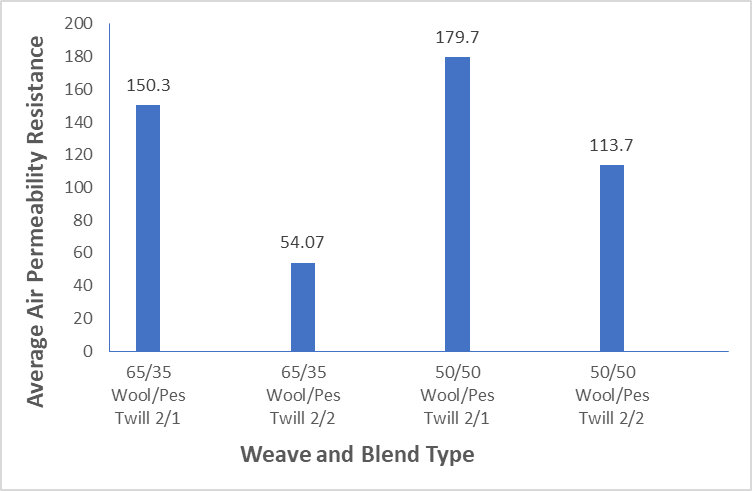

When examining the measurement results in Table 2, it is observed that fabrics with a 2/1 twill weave structure (especially K3) exhibit higher air permeability resistance values compared to fabrics with a 2/2 twill weave structure. This can be explained by the longer yarn floats in the 2/1 twill weave structure and the resulting increase in micro-voids within the fabric that allow air flow. In the 2/2 twill structure, the more balanced distribution of binding points limits porosity, thereby reducing air permeability resistance.

When examining the effect of the blend ratio on air permeability resistance, fabrics with a 50/50 blend ratio, particularly sample K3, are found to achieve higher air permeability resistance values. Figure 2 shows air permeability resistance values that vary according to the type of weave.

Among the samples examined, the thinnest fabric is K3 (0.216 mm), which has the highest air permeability resistance value. The thickest fabric, K4 (0.286 mm), showed lower air permeability resistance. This indicates that as thickness increases, resistance to air flow increases and air permeability decreases. Therefore, it can be said that there is an inverse relationship between fabric thickness and air permeability.

The use of finer weft yarn (60 Nm) in K3 fabric may have contributed to the formation of more voids within the fabric structure. In contrast, fabrics using thicker yarns (e.g., K4 weft yarn is 62 Nm, but the warp yarn is thicker) have been observed to have a tighter weave structure and reduced air permeability resistance. This finding indicates that yarn count has an indirect effect on air permeability, especially when evaluated in conjunction with weave density and thickness.

This study examined the air permeability behavior of wool/polyester blended fabrics with different weave structures, blend ratios, and physical properties, and the findings were evaluated in the context of garment comfort. The results reveal that air permeability is not solely dependent on fiber type, but is shaped by the combined effect of numerous structural parameters such as weave type, weight, yarn density, fabric thickness, and blend ratio.

When evaluated in terms of polyester content, fabrics with a 65/35 wool/polyester blend were found to exhibit lower air permeability resistance values compared to fabrics with a 50/50 blend.

If we examine this relationship using a correlation analysis with fabric types, with air permeability resistance as the dependent variable and polyester content as the independent variable, we obtain the relationship shown in Table 3.

Figure 2. Effect of Weave Type and Blend Ratio on Air Permeability Resistance

Table 3. Correlation between weave type, blend ratio, and air permeability resistance

|

|

Weave Type |

Blend Ratio |

Average Air Permeability Resistance |

|

Weave Type |

1 |

|

|

|

Blend Ratio |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Average Air Permeability |

-0.865195699 |

0.474809672 |

1 |

Figure 3. Polyester Ratio and Air Permeability Resistance

The correlation analysis presented in Table 3 shows a positive relationship between the mixture ratio and air permeability resistance, and a negative but more significant relationship between the weave type and air permeability resistance compared to the mixture ratio. As shown in Figure 3, air permeability resistance values increase significantly with increasing polyester content. Therefore, increased polyester content reduces air permeability by increasing resistance to air flow in the fabric structure. This is true for both types of weave used in the analysis. This can be attributed to polyester fiber having a smoother, lower-volume, and less porous fiber morphology. The naturally curled and voluminous structure of wool fibers creates spaces conducive to air passage between fibers and yarns, while an increase in the polyester ratio causes these spaces to decrease and the fabric structure to become more compact. Therefore, increased polyester content increases resistance to air flow within the fabric, reducing air permeability.

4. Conclusions

In the study, when air permeability values were evaluated in terms of garment comfort, a direct relationship could be established with breathability, one of the fundamental components of thermophysiological comfort. High air permeability facilitates heat and moisture transfer between the body and the environment, contributing to the removal of sweat vapor from the environment. In this context, it can be said that fabrics with lower weight, finer weave, looser construction, and a relatively higher wool content are more suitable for garment types where temperature and moisture regulation are important.

In contrast, the fact that fabrics with a high polyester content exhibit lower air permeability suggests that they may offer advantages in applications where wind permeability needs to be limited or where more controlled heat retention is desired. This situation demonstrates that air permeability does not always need to be at its maximum level, but rather at a level appropriate for the intended use, which is decisive for garment comfort.

As a result, it has been determined that an increase in the polyester content reduces air permeability, while the wool content and accompanying structural properties increase air permeability, thereby positively supporting garment comfort. These findings indicate that in the design of wool/polyester blended fabrics, the blend ratio and structural parameters must be optimized together based on the targeted comfort requirements.

Future studies should focus on determining the optimal fiber ratios in wool-polyester blends and examining the effects of sustainable fiber alternatives on air permeability. At the same time, data on thermal comfort properties can be collected through surveys from individuals who will test actual clothing products, and this data can also be analyzed.

References [1] Havenith, G. (2015). Clothing and thermal

comfort. Textile Progress, 47(2), 1–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405167.2015.1023512 [2] Bishop, P. (2018). Textile

comfort and performance. Textile Progress, 50(2), 75–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405167.2018.1439984 [3] International Organization for

Standardization. (1995). ISO 9237: Textiles—Determination of air

permeability. ISO. [4] Kadolph, S. J. (2016). Textiles (12th ed.).

Pearson. [5] Fan, J., & Hunter, L.

(2009). Engineering apparel fabrics and garments. Woodhead

Publishing. [6] Özdil, N., & Marmaralı, A.

(2017). Fabric structural parameters and air permeability. Tekstil ve

Konfeksiyon, 27(3), 213–220. [7] Das, A., Alagirusamy, R.,

& Kothari, V. K. (2019). Textile science and technology. Woodhead

Publishing. [8] Ajmeri, J. R., & Ajmeri,

C. J. (2016). Textile finishing. CRC Press. [9] Uçar, N., & Ertuğrul, S.

(2018). Air permeability measurement methods. Tekstil ve

Konfeksiyon, 30(1), 1–9. [18] Das, A., & Alagirusamy,

R. (2018). Science in clothing comfort. Woodhead

Publishing. [19] Havenith, G., & Fiala, D.

(2016). Thermal comfort prediction. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 60(2), 231–243.

https://doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/mev102

Georgia Reader Reply

Et rerum totam nisi. Molestiae vel quam dolorum vel voluptatem et et. Est ad aut sapiente quis molestiae est qui cum soluta. Vero aut rerum vel. Rerum quos laboriosam placeat ex qui. Sint qui facilis et.